|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nearly 4

in 10

African

American

children

live in

areas

with

poor

environmental,

social

and

health

factors

compared

to 1 in

10 white

children,

according

to an

index

that

tracks

neighborhood-level

data.

(APPhotos

by WONG

MAYE-E) |

| |

Medical

Racism

in

History

By KAT

STAFFORD,

AARON

MORRISON,

and

ANNIE MA

apnews.com

The

health

inequities

documented

in this

project

have

their

roots in

a long

history

of

medical

racism.

The AP

has

collected

a small

sample

of that

history

related

to every

phase of

life.

Birth:

Gynecology

James

Marion

Sims, a

19th

century

Alabama

surgeon

heralded

as the

father

of

modern

gynecology,

pioneered

a

treatment

for

vesicovaginal

fistulas,

a

condition

that

affects

bladder

control

and

fertility

in

women.

Between

1845 and

1849,

Sims

carried

out the

once-experimental

surgical

treatment

on a

dozen

enslaved

women

without

the use

of

anesthesia.

He has

been

both

defended

as a

product

of his

era and

panned

as

unethical

and

inhumane.

Sims’

belief

that

Black

people

could

endure

more

pain

than

white

people

is

considered

a form

of

racism

and

still

present

in the

field of

medicine.

From

medical

school

students

of

various

racial

and

ethnic

backgrounds

to

primary

care

providers

of small

and

large

practices,

this

bias has

adversely

impacted

the

health

outcomes

of Black

Americans.

It’s

also a

source

of Black

American

skepticism

of

modern

medicine.

Childhood:

Behavioral

Treatment

Behavioral

challenges

in Black

children,

throughout

history

and

typically

in

educational

settings,

have

been met

with

inequitable,

inhumane

and even

extreme

treatment.

Systemic

racism

in

behavioral

counseling

and

psychotherapy

for

school-age

children

has

meant

lifelong

adverse

consequences

for

generations

of Black

children

– from

the

funneling

of Black

students

with

learning

disabilities

into

special

education

tracks

that

lack

resources

and

overreliance

on

suspension

and

expulsion

to

institutionalization

and

experimental

brain

operations.

Dr.

Orlando

J.

Andy’s

work at

the

University

of

Mississippi

Medical

School

in the

1960s is

one

example.

The

neurosurgeon

testified

that he

performed

30 to 40

lobotomies

and

other

brain

operations

on Black

children

and

other

people

with

behavioral

problems

who had

been

institutionalized.

Although

Andy

said his

operations

were a

last

resort

for

patients

who

lived

with

uncontrolled

destructive

hyperactivity,

the

procedure

was

performed

on

institutionalized

Black

boys as

young as

6. Some

patients

lived

the rest

of their

lives

with

deteriorated

intellectual

capacity.

Teen

Years:

Adultification

Black

children

and

teens

are

often

perceived

as much

older

than

they

are.

Because

of this

bias

known as

“adultification,”

they get

viewed

as less

innocent

and less

deserving

of

empathy

–

resulting

in

harsher,

disparate

treatment

in

health

care and

other

systems.

The

attitudes

date

back to

slavery,

when

Black

children

as young

as 2

were

made to

work and

punished

for

developmentally

appropriate

child

behavior,

according

to

scholars

Michael

J. Dumas

and

Joseph

Derrick

Nelson.

Research

shows

these

attitudes

still

drive

disparities

in

outcomes

for

Black

children

and

teens. A

Yale

study

found

Black

children

are 1.8

times

more

likely

to be

physically

restrained

in a

hospital

emergency

room

than

white

kids, a

gap that

may be

driven

by

hospital

staff’s

view of

Black

children.

Georgetown

researchers

have

found

that

adultification

of Black

girls is

linked

to them

being

treated

more

harshly

in

school.

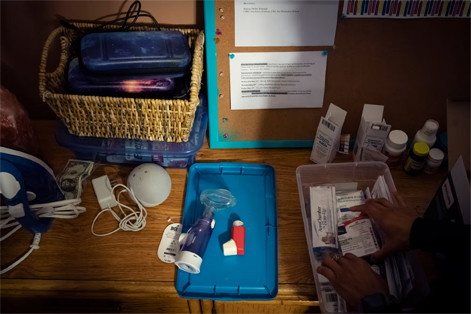

Catherine

Manson

sorts

through

asthma

medication

for her

children

in

Hartford,

Conn.,

on May

25,

2022.

(APPhotos

by WONG

MAYE-E)

Adulthood:

Studying

black

bodies

University

of

Cincinnati

researchers

led an

experiment

from

1960 to

1972

that

exposed

about 90

poor,

mostly

Black,

terminal

cancer

patients

to

extreme

levels

of

radiation

without

their

consent.

The

Department

of

Defense

funded

it as

part of

Cold War

radiation

experiments,

according

to

Associated

Press

stories.

Dr.

Eugene

Saenger,

one of

the

chief

researchers,

said the

study

was

meant to

find

experimental

treatments

for

patients

with

inoperable

cancer

to see

if he

could

stop the

growth

of

tumors.

But the

patients

and

their

families

said

they

were not

fully

informed

of the

risks or

asked to

sign

consent

forms.

They

also

weren’t

told of

the

Defense

Department’s

involvement

or that

the

results

would be

used to

learn

what

might

happen

to

troops

exposed

to

radiation.

A

federal

court

ruling

noted

the

patients

were

told

they

were

receiving

radiation

for

their

cancer.

The

families’

attorneys

said

many of

the

patients

died

after

the

radiation

or

experienced

shortened

life

expectancies.

A judge

approved

a $5.4

million

settlement

for the

families.

Death:

Stealing

black

bodies

Even in

death,

Black

Americans

haven’t

escaped

racist

acts

denying

them the

dignity

their

final

resting

places

should

have

afforded

them.

Graveyard

diggers

were

often

hired to

exhume

and

remove

the

bodies

of Black

people

for the

sake of

medical

research

and

studies,

unbeknownst

to

family

members.

Harriet

Washington,

author

of the

book

“Medical

Apartheid,”

noted

that

Black

graveyards

were

regularly

targeted

–

including

by Dr.

John D.

Goodman,

who in

1829

wrote

that he

paid the

manager

of a

public

graveyard

“for the

privilege

of

‘emptying

the

pits’ of

about 50

to 85

cadavers

a month

during

each

‘dissection

season.’”

Bodies

were

typically

exhumed

during

the

cooler

months

to align

with the

academic

year.

Washington

wrote

that

historian

Todd

Savitt

said

Black

people

were

well

aware of

the

grave

robbery

that

occurred,

as

evidenced

by one

elderly,

enslaved

Virginia

woman

who once

said:

“Please

God, I

hope

when I

die,

it’ll be

the

summertime.”

Digital

Presentation

Credits

Producers:

Samantha

Shotzbarger,

Josh

Housing

Data

Analysis:

Angeliki

Kastanis

Text

Editing:

Anna Jo

Bratton,

Andale

Gross

Illustrations:

Peter

Hamlin

Design

and

Development:

Linda

Gorman,

Kati

Perry

and

Eunice

Esomonu

Audience

Coordination

and

Production:

Ed

Medeles,

Elise

Ryan,

Almaz

Abedje

and

Sophie

Rosenbaum

Creative

Development:

Raghuram

Vadarevu

Project

Management:

Andale

Gross

Project

Vision

and

Development:

Kat

Stafford

Stafford,

based in

Detroit,

is a

national

investigative

race

writer

for the

AP’s

Race and

Ethnicity

team.

She was

a 2022

Knight-Wallace

Reporting

Fellow

at the

University

of

Michigan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|